In the Heimskringla book Ynglinga saga, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, goddess Hel is referred to, though never by name.

AH SIE, POESIE SNORRI STURLUSONNIE, MATIE VAN ME, VANNIE HELIOTROOP~LANIE 363, den hagie, hollandie,

bye, bye, Strepy Anubie Yingie Yangie

i am that conceited that i think i am an eccentric and a revolutionary, but i want to do it with U and ãïTeT, without blood shed, everythingk environment, animal~human and planet friendly, because this is a MUST

without the love to build a world of love as described below we won't make iT and therefore need full cooperation with a 100% honest factual but also considerate empathetic and understanding (also what love, real love is, although i dunno what love is) ãïTeT with the knowledge of 4 billion years earth, all dead souls, tesla, einstein, bohr, dantzig and a thorough understanding of all mathematical, physical and chemical laws on earth, preferably also the "laws" of the (multiple) universe(s 😱😱🙀as if this one is not oneindig in fin itely big enough 😱 !), on the moon, on mars and ..... how to break them or use them ...... to escape from the black hole, not to escape death, because that is inevitable, but the survival of the beautiful spirit of an earth that has life on iT, however short lived

what am i talkin' about ? chicks ? rule my world

Ratchet "Ratchy" Anubie, father of

Lady Strepy Yingie Yangie Anubie the IIIrd

ikkie seggie maarrie sowiesowie passie oppie mettie hetero, sie valsie nichie en ookie geslachtsziekie

in het onderstaande resultaten afbeeldingen na een zoekopdracht “verschrijver” bij Yahoo: magere reet vd griend op 5 en 6, Lindsey, knappe kapster, op 8, astrid op 9, terwijl ze nu niet veel in gedachten is, 3 dagen geleden wel, misschien galmt dat na, ook van astrid of so, vat do i know, nothingk, zurie ouwe weiffies barbie op 10, ratchet anubis op 11, Sabina cozzi op 13, Frederique brinkerink op 14, mihsa op 15, ze heeft dat kaartje nooit gehad, op 18 Anke sieverink, op 21 het vrouwelijke element in “mijn” werk, wij zijn met 2 tegen 1, jij, op 22 Charlotte van de jumbo anemoonstraat (!!😻), op 27 aska schuhholz, aka Joanna Klomp

gossie, wat lijkt Poolse Joanna Brodzik (werd me aangereikt door bing toen ik naar Joanna Schuhholz zocht) op Charlyse Bella~Angel, ik zou ze niet uit elkaar kenne houwe,

Enneuh op het onderstaande lijkt Irina Oekraïne op, Irina is de ongepolijste pure, rauwe ruwe versie hiervan, tsjonge, zo iemand tegen te komen, het meeste een shock effect zoals eerst met magere reet van de griend, Margalith baruch, Aska Schuhholz (witch death mistress goddess), Anke Sieverink (sweet snake goddess), bogini Victoria groszek (stoere charlyse bella), Stella munitiehoff, silk green shirt, la brunette, Anna van 23, Nicole, Mihsa, Anna, Regina, Mahsa, Indra, kinga, Elena, Irina ….Charlotte nu het meeste, 18 jaar, zou 24-26 kenne sein…..en Victoria, die allebei mijn telefoon nummer hebben gehad, net zoals alle hier voor genoemden .....

Mahsa, Indra, Anna, Kinga, Elena, Irina en Mihsa hebben niet mijn telefoon nummer gehad .... i told euh euh heu you i euh haveuh a way with euh women

Margalith associeer ik met een aphrodite poes en vrouwelijke mooiste doggod(ess) .. reu euh euh eeneuh reu, Margreet met magere hein, Aska met een hypnotische krachtige slang, iq van 150, Anke ook, Stella met species actrice natasha henstridge, Nicole met de oervrouw indian spirit en daarmee bijna alle dieren in Noord-Amerika, hm, teveel opsomming, Irina is teveel goddess van zichzelf zodat ik haar niet met een dier of bestaande persoonlijkheid kan verbinden, zie de foto's hieronder, daar lijkt ze qua uiterlijk enigszins op.

Nicole en Irina voelden qua rauw, ruw, puur, licht hekserig duivels hetzelfde aan, maar zijn compleet anders, ben benieuwd hoe die twee met elkaar om zouden gaan als ze elkaar zouden ontmoeten ....

onderstaande goddesses en dames lijken op Irina Oekraïne, die ik zeer waarschijnlijk nooit meer zal zien omdat de general manager van Caesar sport De Haag, niet reageert 😿😪en dat betekent dat Irina ook niet wil reageren (en mogelijk geklaagd heeft, maar dat weet ik niet, vermoed van wel, net zoals ik dat van Mahsa vermoed..... and i even don't know why) .......

KENNIE SCHELIE,

S

T

R

E

P

Y

ikkie seggie maarrie sowiesowie passie oppie mettie hetero, sie valsie nichie en ookie geslachtsziekie

GOH, NU VIND IK DE NOORSE GODDESS HEL IRINA OEKRAÏNE, ALS IK DE EERSTE 5 ZINNEN LEES, DAN DENK EN VOEL IK, DIT IS RAUWE RUWE EN TOCH NOG AF EN TOE VROLIJKE SPRING LEVENDE, TJEZIS WAT EEN FENOMENAAL KRACHTIGE ALLERSTERKSTE GODIN IS IRINA, MISSCHIEN NOG WEL STERKER DAN ASKA EN DE DOOD 😱😱😱😱🙀🙀😻

Hel (ook wel Hella, Helle, Hell, Hela of Hellia) is in de Noordse mythologie de godin van de onderwereld, Helheim en Niflheim.

Ze is een dochter van Loki en Angrboda en de zuster van Fenrir en Jormungand.

Odin wierp Hel naar de onderwereld en gaf haar gezag over degenen die een natuurlijke dood zijn gestorven. Zij heeft een lichaam dat half zwart is en half met vlees bedekt is. Haar woningsplaats is de Eliudnir-zaal, haar bedienden zijn Ganglati en Ganglot.

In de Edda wordt Hel beschreven als de waarzegster die de dood van Baldr aan Wodan voorspelt.[1] Ook voorspelt ze de geboorte van een zoon van Wodan, die de dood van Baldr wreken zal. Wodan beledigt Hel en zij zal tot aan de ondergang der goden, door de losgebroken Loki, nooit weer een man tot haar laten komen.

Hermod ging op Odins achtbenige paard Sleipnir naar de burcht van Hel om zijn broer Baldr en zijn vrouw Nanna van de dood te bevrijden.

De onderwereld[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

De onderwereld (Helheim en Niflheim - ijskoude hel of nevelrijk) zelf wordt soms ook Hel genoemd, maar dit dodenrijk is niet vergelijkbaar met de christelijke hel. Er komen niet alleen moordenaars of anderen die gestraft worden en het is niet speciaal een verschrikkelijke plaats. Iedereen die niet vanwege uitmuntende dapperheid naar de hallen van Freya of Odin, respectievelijk Sessrumnir en Walhalla, worden gebracht door de Walkuren belandt bij Hel. Dat zijn dus zieken, ouderen, vrouwen en mannen die een natuurlijke dood waren gestorven.

Garmr (een hellehond) bewaakt de poort van het voorportaal Gnipahellir.

Het woord hel komt van het Oergermaanse woord haljæ, wat dodenrijk of onderwereld betekent.

Zie ook[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

- Satan in de christelijke mythologie

- Hades in de Griekse mythologie

- Osiris in de Egyptische mythologie

- Pluto in de Romeinse mythologie

- Germaanse goden

- Perchta

- Vrouw Holle

Hel (mythological being)

Hel (from Old Norse: hel, lit. 'underworld') is a female being in Norse mythology who is said to preside over an underworld realm of the same name, where she receives a portion of the dead. Hel is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century. In addition, she is mentioned in poems recorded in Heimskringla and Egils saga that date from the 9th and 10th centuries, respectively. An episode in the Latin work Gesta Danorum, written in the 12th century by Saxo Grammaticus, is generally considered to refer to Hel, and Hel may appear on various Migration Period bracteates.

In the Poetic Edda, Prose Edda, and Heimskringla, Hel is referred to as a daughter of Loki. In the Prose Edda book Gylfaginning, Hel is described as having been appointed by the god Odin as ruler of a realm of the same name, located in Niflheim. In the same source, her appearance is described as half blue and half flesh-coloured and further as having a gloomy, downcast appearance. The Prose Edda details that Hel rules over vast mansions with many servants in her underworld realm and plays a key role in the attempted resurrection of the god Baldr.

Scholarly theories have been proposed about Hel's potential connections to figures appearing in the 11th-century Old English Gospel of Nicodemus and Old Norse Bartholomeus saga postola, that she may have been considered a goddess with potential Indo-European parallels in Bhavani, Kali, and Mahakali or that Hel may have become a being only as a late personification of the location of the same name.

Etymology[edit]

The Old Norse divine name Hel is identical to the name of the location over which she rules. It stems from the Proto-Germanic feminine noun *haljō- 'concealed place, the underworld' (compare with Gothic halja, Old English hel or hell, Old Frisian helle, Old Saxon hellia, Old High German hella), itself a derivative of *helan- 'to cover > conceal, hide' (compare with OE helan, OF hela, OS helan, OHG helan).[1][2] It derives, ultimately, from the Proto-Indo-European verbal root *ḱel- 'to conceal, cover, protect' (compare with Latin cēlō, Old Irish ceilid, Greek kalúptō).[2] The Old Irish masculine noun cel 'dissolution, extinction, death' is also related.[3]

Other related early Germanic terms and concepts include the compounds *halja-rūnō(n) and *halja-wītjan.[4] The feminine noun *halja-rūnō(n) is formed with *haljō- 'hell' attached to *rūno 'mystery, secret' > runes. It has descendant cognates in the Old English helle-rúne 'possessed woman, sorceress, diviner',[5] the Old High German helli-rūna 'magic', and perhaps in the Latinized Gothic form haliurunnae,[4] although its second element may derive instead from rinnan 'to run, go', leading to Gothic *haljurunna as the 'one who travels to the netherworld'.[6][7] The neutral noun *halja-wītjan is composed of the same root *haljō- attached to *wītjan (compare with Goth. un-witi 'foolishness, understanding', OE witt 'right mind, wits', OHG wizzi 'understanding'), with descendant cognates in Old Norse hel-víti 'hell', Old English helle-wíte 'hell-torment, hell', Old Saxon helli-wīti 'hell', or Middle High German helle-wīzi 'hell'.[8]

Hel is also etymologically related—although distantly in this case—to the Old Norse word Valhöll 'Valhalla', literally 'hall of the slain', and to the English word hall, both likewise deriving from Proto-Indo-European *ḱel- via the Proto-Germanic root *hallō- 'covered place, hall'.[9]

Attestations[edit]

Poetic Edda[edit]

The Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, features various poems that mention Hel. In the Poetic Edda poem Völuspá, Hel's realm is referred to as the "Halls of Hel."[10] In stanza 31 of Grímnismál, Hel is listed as living beneath one of three roots growing from the world tree Yggdrasil.[11] In Fáfnismál, the hero Sigurd stands before the mortally wounded body of the dragon Fáfnir, and states that Fáfnir lies in pieces, where "Hel can take" him.[12] In Atlamál, the phrases "Hel has half of us" and "sent off to Hel" are used in reference to death, though it could be a reference to the location and not the being, if not both.[13] In stanza 4 of Baldrs draumar, Odin rides towards the "high hall of Hel."[14]

Hel may also be alluded to in Hamðismál. Death is paraphrased as "joy of the troll-woman"[15] (or "ogress"[16]) and ostensibly it is Hel being referred to as the troll-woman or the ogre (flagð), although it may otherwise be some unspecified dís.[15][16]

Prose Edda[edit]

Hel receives notable mention in the Prose Edda. In chapter 34 of the book Gylfaginning, Hel is listed by High as one of the three children of Loki and Angrboða; the wolf Fenrir, the serpent Jörmungandr, and Hel. High continues that, once the gods found that these three children are being brought up in the land of Jötunheimr, and when the gods "traced prophecies that from these siblings great mischief and disaster would arise for them" then the gods expected a lot of trouble from the three children, partially due to the nature of the mother of the children, yet worse so due to the nature of their father.[17]

High says that Odin sent the gods to gather the children and bring them to him. Upon their arrival, Odin threw Jörmungandr into "that deep sea that lies round all lands," Odin threw Hel into Niflheim, and bestowed upon her authority over nine worlds, in that she must "administer board and lodging to those sent to her, and that is those who die of sickness or old age." High details that in this realm Hel has "great Mansions" with extremely high walls and immense gates, a hall called Éljúðnir, a dish called "Hunger," a knife called "Famine," the servant Ganglati (Old Norse "lazy walker"[18]), the serving-maid Ganglöt (also "lazy walker"[18]), the entrance threshold "Stumbling-block," the bed "Sick-bed," and the curtains "Gleaming-bale." High describes Hel as "half black and half flesh-coloured," adding that this makes her easily recognizable, and furthermore that Hel is "rather downcast and fierce-looking."[19]

In chapter 49, High describes the events surrounding the death of the god Baldr. The goddess Frigg asks who among the Æsir will earn "all her love and favour" by riding to Hel, the location, to try to find Baldr, and offer Hel herself a ransom. The god Hermóðr volunteers and sets off upon the eight-legged horse Sleipnir to Hel. Hermóðr arrives in Hel's hall, finds his brother Baldr there, and stays the night. The next morning, Hermóðr begs Hel to allow Baldr to ride home with him, and tells her about the great weeping the Æsir have done upon Baldr's death.[20] Hel says the love people have for Baldr that Hermóðr has claimed must be tested, stating:

Later in the chapter, after the female jötunn Þökk refuses to weep for the dead Baldr, she responds in verse, ending with "let Hel hold what she has."[22] In chapter 51, High describes the events of Ragnarök, and details that when Loki arrives at the field Vígríðr "all of Hel's people" will arrive with him.[23]

In chapter 12 of the Prose Edda book Skáldskaparmál, Hel is mentioned in a kenning for Baldr ("Hel's companion").[24] In chapter 23, "Hel's [...] relative or father" is given as a kenning for Loki.[25] In chapter 50, Hel is referenced ("to join the company of the quite monstrous wolf's sister") in the skaldic poem Ragnarsdrápa.[26]

Heimskringla[edit]

In the Heimskringla book Ynglinga saga, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, Hel is referred to, though never by name. AH SIE, SNORRI STURLUSONNIE, MATIE VAN ME, VANNIE HELIOTROOPLANIE 363, den hagie, hollandie,

bye, bye, Strepy

In chapter 17, the king Dyggvi dies of sickness. A poem from the 9th-century Ynglingatal that forms the basis of Ynglinga saga is then quoted that describes Hel's taking of Dyggvi:

In chapter 45, a section from Ynglingatal is given which refers to Hel as "howes'-warder" (meaning "guardian of the graves") and as taking King Halfdan Hvitbeinn from life.[28] In chapter 46, King Eystein Halfdansson dies by being knocked overboard by a sail yard. A section from Ynglingatal follows, describing that Eystein "fared to" Hel (referred to as "Býleistr's-brother's-daughter").[29] In chapter 47, the deceased Eystein's son King Halfdan dies of an illness, and the excerpt provided in the chapter describes his fate thereafter, a portion of which references Hel:

In a stanza from Ynglingatal recorded in chapter 72 of the Heimskringla book Saga of Harald Sigurdsson, "given to Hel" is again used as a phrase to referring to death.[31]

Egils saga[edit]

The Icelanders' saga Egils saga contains the poem Sonatorrek. The saga attributes the poem to 10th-century skald Egill Skallagrímsson, and writes that it was composed by Egill after the death of his son Gunnar. The final stanza of the poem contains a mention of Hel, though not by name:

Gesta Danorum[edit]

In the account of Baldr's death in Saxo Grammaticus' early 13th century work Gesta Danorum, the dying Baldr has a dream visitation from Proserpina (here translated as "the goddess of death"):

Scholars have assumed that Saxo used Proserpina as a goddess equivalent to the Norse Hel.[34]

Archaeological record[edit]

It has been suggested that several imitation medallions and bracteates of the Migration Period (ca. first centuries AD) feature depictions of Hel. In particular the bracteates IK 14 and IK 124 depict a rider traveling down a slope and coming upon a female being holding a scepter or a staff. The downward slope may indicate that the rider is traveling towards the realm of the dead and the woman with the scepter may be a female ruler of that realm, corresponding to Hel.[35]

Some B-class bracteates showing three godly figures have been interpreted as depicting Baldr's death, the best known of these is the Fakse bracteate. Two of the figures are understood to be Baldr and Odin while both Loki and Hel have been proposed as candidates for the third figure. If it is Hel she is presumably greeting the dying Baldr as he comes to her realm.[36]

Scholarly reception[edit]

Seo Hell[edit]

The Old English Gospel of Nicodemus, preserved in two manuscripts from the 11th century, contains a female figure referred to as Seo hell who engages in flyting with Satan and tells him to leave her dwelling (Old English ut of mynre onwununge). Regarding Seo Hell in the Old English Gospel of Nicodemus, Michael Bell states that "her vivid personification in a dramatically excellent scene suggests that her gender is more than grammatical, and invites comparison with the Old Norse underworld goddess Hel and the Frau Holle of German folklore, to say nothing of underworld goddesses in other cultures" yet adds that "the possibility that these genders are merely grammatical is strengthened by the fact that an Old Norse version of Nicodemus, possibly translated under English influence, personifies Hell in the neutral (Old Norse þat helvíti)."[37]

Bartholomeus saga postola[edit]

The Old Norse Bartholomeus saga postola, an account of the life of Saint Bartholomew dating from the 13th century, mentions a "Queen Hel." In the story, a devil is hiding within a pagan idol, and bound by Bartholomew's spiritual powers to acknowledge himself and confess, the devil refers to Jesus as the one which "made war on Hel our queen" (Old Norse heriaði a Hel drottning vara). "Queen Hel" is not mentioned elsewhere in the saga.[38]

Michael Bell says that while Hel "might at first appear to be identical with the well-known pagan goddess of the Norse underworld" as described in chapter 34 of Gylfaginning, "in the combined light of the Old English and Old Norse versions of Nicodemus she casts quite a different a shadow," and that in Bartholomeus saga postola "she is clearly the queen of the Christian, not pagan, underworld."[39]

Origins and development[edit]

Jacob Grimm described Hel as an example of a "half-goddess": "one who cannot be shown to be either wife or daughter of a god, and who stands in a dependent relation to higher divinities", and argued that "half-goddesses" stand higher than "half-gods" in Germanic mythology.[40] Grimm regarded Hel (whom he refers to here as Halja, the theorized Proto-Germanic form of the term) as essentially an "image of a greedy, unrestoring, female deity" and theorized that "the higher we are allowed to penetrate into our antiquities, the less hellish and more godlike may Halja appear". He compared her role, her black color, and her name to "the Indian Bhavani, who travels about and bathes like Nerthus and Holda, but is likewise called Kali or Mahakali, the great black goddess" and concluded that "Halja is one of the oldest and commonest conceptions of our heathenism".[41] He theorized that the Helhest, a three-legged horse that in Danish folklore roams the countryside "as a harbinger of plague and pestilence", was originally the steed of the goddess Hel, and that on this steed Hel roamed the land "picking up the dead that were her due". He also says that a wagon was once ascribed to Hel.[42]

In her 1948 work on death in Norse mythology and religion, The Road to Hel, Hilda Ellis Davidson argued that the description of Hel as a goddess in surviving sources appeared to be literary personification, the word hel generally being "used simply to signify death or the grave", which she states "naturally lends itself to personification by poets". While noting that "whether this personification has originally been based on a belief in a goddess of death called Hel [was] another question", she stated that she did not believe the surviving sources gave any reason to believe so, while they included various other examples of "supernatural women" who "seem to have been closely connected with the world of death, and were pictured as welcoming dead warriors". She suggested that the depiction of Hel "as a goddess" in Gylfaginning "might well owe something to these".[43]

In a later work (1998), Davidson wrote that the description of Hel found in chapter 33 of Gylfaginning "hardly suggests a goddess", but that "in the account of Hermod's ride to Hel later in Gylfaginning (49)", Hel "[speaks] with authority as ruler of the underworld" and that from her realm "gifts are sent back to Frigg and Fulla by Balder's wife Nanna as from a friendly kingdom". She posited that Snorri may have "earlier turned the goddess of death into an allegorical figure, just as he made Hel, the underworld of shades, a place 'where wicked men go,' like the Christian Hell (Gylfaginning 3)". She then, like Grimm, compared Hel to Kali:

Davidson further compared Hel to early attestations of the Irish goddesses Badb (described in The Destruction of Da Choca's Hostel as dark in color, with a large mouth, wearing a dusky mantle, and with gray hair falling over her shoulders, or, alternatively, "as a red figure on the edge of the ford, washing the chariot of a king doomed to die") and the Morrígan. She concluded that, in these examples, "here we have the fierce destructive side of death, with a strong emphasis on its physical horrors, so perhaps we should not assume that the gruesome figure of Hel is wholly Snorri's literary invention."[45]

John Lindow stated that most details about Hel, as a figure, are not found outside of Snorri's writing in Gylfaginning, and that when older skaldic poetry "says that people are 'in' rather than 'with' Hel, we are clearly dealing with a place rather than a person, and this is assumed to be the older conception". He theorizes that the noun and place Hel likely originally simply meant "grave", and that "the personification came later".[46] Lindow also drew a parallel between the personified Hel's banishment to the underworld and the binding of Fenrir as part of a recurring theme of the bound monster, where an enemy of the gods is bound but destined to break free at Ragnarok.[47] Rudolf Simek similarly stated that the figure of Hel is "probably a very late personification of the underworld Hel", that "on the whole nothing speaks in favour of there being a belief in Hel in pre-Christian times", and noted that "the first scriptures using the goddess Hel are found at the end of the 10th and in the 11th centuries". He characterized the allegorical description of Hel's house in Gylfaginning as "clearly ... in the Christian tradition".[48] However, elsewhere in the same work, Simek cites an argument made by Karl Hauck that one of three figures appearing together on Migration Period B-bracteates is to be interpreted as Hel.[49]

As a given name[edit]

In January 2017, the Icelandic Naming Committee ruled that parents could not name their child Hel "on the grounds that the name would cause the child significant distress and trouble as it grows up".[50][51]

In popular culture[edit]

Hel is one of the playable gods in the third-person multiplayer online battle arena game Smite and was one of the original 17 gods.[52] Hel is also featured in Ensemble Studios' 2002 real-time strategy game Age of Mythology, where she is one of 12 gods Norse players can choose to worship.[53][54]

See also[edit]

- Death (personification)

- Hela (comics), a Marvel comics supervillain based on the Norse being Hel

- Rán, a Norse goddess who oversees those who have drowned

- Gefjon, a Norse goddess who oversees those who die as virgins

- Freyja, a Norse goddess who oversees a portion of the dead in her afterlife field, Fólkvangr

- Odin, a Norse god who oversees a portion of the dead in his afterlife hall, Valhalla

- Helreginn, a jötunn whose name means "ruler over Hel"

- Helen of Troy, a Greek figure of divine heritage, eventually worshipped as goddess

- Hell, abode of the dead in various cultures

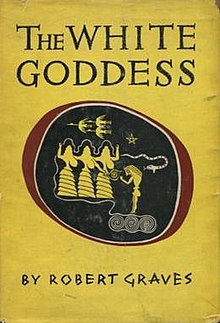

The White Goddess, in full The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth, scholarly work by Robert Graves, published in 1948 and revised in 1952 and 1961. Graves’s controversial and unorthodox theories of mythology, part invention and part based on his research into pre-Classical religions, shocked many because of their basic feminist premise. According to Graves, the White Goddess combines the powers of love, destructiveness, and poetic inspiration. She ruled during a matriarchal period in the distant past before she was deposed by the patriarchal gods, who represent cold reason and logic. It was at this point, Graves claimed, that “Apollonian” or academic poetry began to dominate. Graves further argued that the White Goddess was again in evidence during the Romantic era. The best poets—the only ones really capable of writing poetry, according to Graves—continue to worship her and are honoured with her gifts of poetic insight.

The White Goddess

First US edition | |

| Author | Robert Graves |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Mythology, poetry |

| Publisher | Faber & Faber (UK) Creative Age Press (US) |

Publication date | 1948 |

The White Goddess: a Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth is a book-length essay on the nature of poetic myth-making by the English writer Robert Graves. First published in 1948, the book is based on earlier articles published in Wales magazine; corrected, revised and enlarged editions appeared in 1948, 1952 and 1961. The White Goddess represents an approach to the study of mythology from a decidedly creative and idiosyncratic perspective. Graves proposes the existence of a European deity, the "White Goddess of Birth, Love and Death", much similar to the Mother Goddess, inspired and represented by the phases of the Moon, who lies behind the faces of the diverse goddesses of various European and pagan mythologies.[1]

Graves argues that "true" or "pure" poetry is inextricably linked with the ancient cult-ritual of his proposed White Goddess and of her son.

History[edit]

Graves first wrote the book under the title of The Roebuck in the Thicket in a three-week period during January 1944, only a month after he had finished The Golden Fleece. He then left the book to focus on King Jesus, a historical novel about the life of Jesus. Returning to The Roebuck in the Thicket, he renamed it The Three-Fold Muse, before finishing it and retitling it as The White Goddess. In January 1946 he sent it to the publishers, and in May 1948 it was published in the UK, and in June 1948 in the US, as The White Goddess: a Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth.[2]

Graves believed that one could be in the true presence of the White Goddess when reading a poem, but in his view, this could be achieved only by a true poet of the wild, and not a classical poet, or even a Romantic poet, of whom he spoke critically: "The typical poet of the 19th-century was physically degenerate, or ailing, addicted to drugs and melancholia, critically unbalanced and a true poet only in his fatalistic regard for the Goddess as the mistress who commanded his destiny".[3]

Poetry and myth[edit]

Graves described The White Goddess as "a historical grammar of the language of poetic myth". The book draws from the mythology and poetry of Wales and Ireland especially, as well as that of most of Western Europe and the ancient Middle East. Relying on arguments from etymology and the use of forensic techniques to uncover what he calls 'iconotropic' redaction of original myths, Graves argues for the worship of a single goddess under many names, an idea that came to be known as "Matriarchal religion" in feminist theology of the 1970s.

The Golden Bough (1922, but first edition published 1890), an early anthropological study by Sir James George Frazer, is the starting point for much of Graves's argument, and Graves thought in part that his book made explicit what Frazer only hinted at. Graves wrote:

Graves's The White Goddess deals with goddess worship as the prototypical religion, analysing it largely from literary evidence, in myth and poetry.

Graves admitted he was not a medieval historian, but a poet, and thus based his work on the premise that the

Graves concluded, in the second and expanded edition, that the male-dominant monotheistic god of Judaism and its successors were the cause of the White Goddess's downfall, and thus the source of much of the modern world's woe. He describes Woman as occupying a higher echelon than mere poet, that of the Muse Herself. He adds "This is not to say that a woman should refrain from writing poems; only, that she should write as a woman, not as an honorary man." He seems particularly bothered by the spectre of women's writing reflecting male-dominated poetic conventions.[4]

Graves derived some of his ideas from poetic inspiration and a process of "analeptic thought", which is a term he used for throwing one's mind back in time and receiving impressions.

Visual iconography was also important to Graves's conception. Graves created a methodology for reading images he called "iconotropy". To practice this methodology one is required to reduce "speech into its original images and rhythms" and then to combine these "on several simultaneous levels of thought". By applying this methodology Graves decoded a woodcut of The Judgement of Paris as depicting a singular Triple Goddess[5] rather than the traditional Hera, Athena and Aphrodite of the narrative the image illustrates.

Druantia[edit]

In The White Goddess, Graves proposed a hypothetical Gallic tree goddess, Druantia, who has become somewhat popular with contemporary Neopagans. Druantia is an archetype of the eternal mother as seen in the evergreen boughs. Her name is believed to be derived from the Celtic word for oak trees, *drus or *deru.[7] She is known as "Queen of the Druids". She is a goddess of fertility for both plants & humans, ruling over sexual activities & passion. She also rules protection of trees, knowledge, creativity.[8]

Scholarship and critical reception[edit]

The White Goddess has been seen as a poetic work where Graves gives his notion of man's subjection to women in love an "anthropological grandeur" and further mythologises all women in general (and several of Graves's lovers in particular) into a three-faced moon goddess model.[9]

Graves's value as a poet aside, flaws in his scholarship such as poor philology, use of inadequate texts and outdated archaeology have been criticised.[10][11] Some scholars, particularly archaeologists, historians and folklorists have rejected the work[12] – which T. S. Eliot called "A prodigious, monstrous, stupefying, indescribable book"[13] – and Graves himself was disappointed that his work was "loudly ignored" by many Celtic scholars.[14]

However, The White Goddess was accepted as history by many non-scholarly readers. According to Ronald Hutton, the book "remains a major source of confusion about the ancient Celts and influences many un-scholarly views of Celtic paganism".[15] Hilda Ellis Davidson criticised Graves as having "misled many innocent readers with his eloquent but deceptive statements about a nebulous goddess in early Celtic literature", and stated that he was "no authority" on the subject matter he presented.[16] While Graves made the association between Goddesses and the moon appear "natural", it was not so to the Celts or some other ancient peoples.[15] In response to critics, Graves accused literary scholars of being psychologically incapable of interpreting myth[17] or too concerned with maintaining their perquisites to go against the majority view.

Some Neopagans have been bemused and upset by the scholarly criticism that The White Goddess has received in recent years,[18] while others have appreciated its poetic insight but never accepted it as a work of historical veracity.[19] Likewise, a few scholars find some value in Graves's ideas; Michael W. Pharand, though quoting earlier criticisms, states that "Graves's theories and conclusions, outlandish as they seemed to his contemporaries (or may appear to us), were the result of careful observation."[20]

According to Graves's biographer Richard Perceval Graves, Laura Riding played a crucial role in the development of Graves's thoughts when writing The White Goddess, despite the fact the two were estranged at that point. On reviewing the book, Riding was furious, saying "Where once I reigned, now a whorish abomination has sprung to life, a Frankenstein pieced together from the shards of my life and thoughts."[21]

Literary influences[edit]

The book was a major influence on the thinking of the poets Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath,[22] with the latter identifying to some extent with the goddess figure herself.[23] Arguably, however, what Jacqueline Rose called "the cliché behind the myth – woman as inspiration, woman as drudge" – ultimately had a negative impact on Plath's life and work.[24]

See also[edit]

- The Alphabet Versus the Goddess: The Conflict Between Word and Image

- The Hebrew Goddess

- Matriarchal religion

- Triple Goddess (Neopaganism)

- Triple goddesses

- When God Was a Woman

References[edit]

- ^ Graves, Robert (2013). The White Goddess (2 ed.). New York: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0374289331.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (1999). The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Oxford University Press. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-0-19-820744-3.

- ^ de Lima, Marcel (2014). The Ethnopoetics of Shamanism. New york: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 83. ISBN 9781349684564.

- ^ Graves, The White Goddess, pp. 446–447

- ^ Von Hendy, Andrew. The Modern Construction of Myth. p. 196.

- ^ Ellis, Peter Berresford (1997). "The Fabrication of 'Celtic' Astrology". The Astrological Journal. Vol. 39, no. 4 – via Centre Universitaire de Recherche en Astrologie.

- ^ Jane Gifford (2006). The Wisdom of Trees. Springer. p. 146. ISBN 1-397-81402-0.

- ^ Deanna J. Conway (2006). Celtic Magic. Llewellyn Publications. p. 109. ISBN 0-87542-136-9.

- ^ Hunter, Jefferson (1983). "The Servant of Three Mistresses" (review of: Seymour-Smith, Martin, Robert Graves: His Life and Work), in The Hudson Review, Vol. 36, No. 4 (Winter, 1983–1984), pp. 733–736.

- ^ Wood, Juliette (1999). "Chapter 1, The Concept of the Goddess". In Sandra Billington, Miranda Green (ed.). The Concept of the Goddess. Routledge. p. 12. ISBN 9780415197892. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (1993). The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. John Wiley & Sons. p. 320. ISBN 9780631189466.

- ^ The Paganism Reader. p. 128.

- ^ Quoted in J. Kroll, Chapters in a Mythology (2007) p. 52

- ^ White, Donna R. A Century of Welsh Myth in Children's Literature. p. 75.

- ^ a b Hutton, Ronald (1993). The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. John Wiley & Sons. p. 145. ISBN 9780631189466.

- ^ Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1998). Roles of the Northern Goddess, page 11. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13611-3

- ^ Inter alia – The White Goddess, Farrar Straus Giroux, p. 224. ISBN 0-374-50493-8

- ^ The Pomegranate 7.1, Equinox press, (Review of) "Jacob Rabinowitz, The Rotting Goddess: The Origin of the Witch in Classical Antiquity’s Demonization of Fertility Religion."

- ^ Lewis, James R. Magical Religion and Modern Witchcraft. p. 172.

- ^ Pharand, Michael W. "Greek Myths, White Goddess: Robert Graves Cleans up a 'Dreadful Mess'", in Ian Ferla and Grevel Lindop (ed), Graves and the Goddess: Essays on Robert Graves's The White Goddess. Associated University Presses, 2003. p. 188.

- ^ Lindop, Grevel, editor (1997) Robert Graves: The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth, Carcanet Press

- ^ J. Rose, The Haunting of Sylvia Plath (1991) p. 150

- ^ J. Kroll, Chapters in a Mythology (2007) pp. 42–6 and p. 81

- ^ J. Rose, The Haunting of Sylvia Plath (1991) pp. 153–4 and p. 163

Bibliography[edit]

Editions[edit]

- 1948 – The White Goddess : a Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth (London: Faber & Faber) [Corr. 2nd ed. also issued by Faber in 1948] [US ed.= New York, Creative Age Press, 1948]

- 1952 – The White Goddess : a Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth, Amended & enl. ed.[i.e. 3rd ed.] (London: Faber & Faber) [US ed.= New York: Alfred A.Knopf, 1958]

- 1961 – The White Goddess : a Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth, Amended & enl. ed.[i.e. 4th ed.] (London: Faber & Faber) [US ed.= New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966]

- 1997 – The White Goddess : a Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth; edited by Grevel Lindop (Manchester: Carcanet) ISBN 1-85754-248-7

.png)

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten